The first line stopped me mid-scroll.

“Not everyone who lost his life in Vietnam died there.”

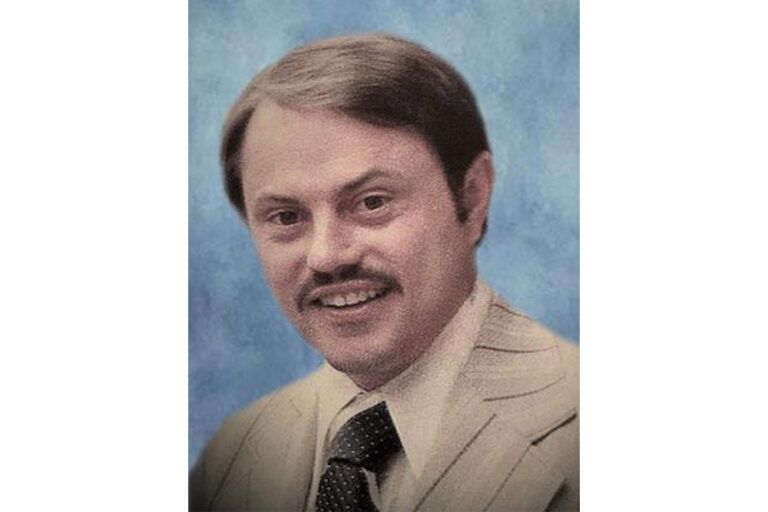

I clicked through to the obituary accompanying a photo of a mustached man, mouth caught in a smile, eyes mischievous.

It was, I’d soon come to understand, vintage William “Bill” Ebeltoft. Soft-hearted. Kind. Generous.

But as his brother, Paul, writes in an obituary published this week in a Dickinson, North Dakota newspaper, Bill “died 50 years after he lost, in Vietnam, all that underpinned his life.”

Today, that life—damaged, complicated, and so clearly loved—is captivating the nation.

Bill’s obituary has gone viral, and it’s easy to see why:

It is difficult to write about Bill. He lived three lives: before, during and after Vietnam. Before Vietnam, Bill was a handsome man, who wore clothing well; a man with white, straight teeth that showed in his ready smile. A state champion trap shooter, a low handicap golfer, a 218-average bowler, a man of quick, earthy wit, with a fondness for children, old men, hunting, fast cars, and a cold Schlitz. He told jokes well.

During Vietnam, he lived with horrors of which he would only seldom speak. Slow Motion Four, Bill’s personal call sign, logged thousands of helicopter flight hours performing Forward Support Base resupply landings, medical evacuations, exfils and gun ship runs. We know of him there mostly through medals for valor he received, and these were many.

The obituary continues with a combat story from February 3, 1969, when Bill’s helicopter came under fire during a mission; his skill and dedication saved the lives of fellow soldiers.

As Paul recounts:

Bill got the medal, of course, but he would have been the last to say anything about it. The citation shows the type of man that he, and many of his brothers-in-arms in Vietnam were; and still are today, albeit battered hard and unfairly by the cruel winds of the times in which they fought.

His time in Vietnam, Paul writes, left Bill a changed man. Bill struggled in civilian life after the war, battling the demons that eventually necessitated a permanent move to a Veteran’s Home in Montana.

If the story of Bill’s life ended there, it would, undoubtedly, be a tragedy.

But as the obituary continues, you realize the story of Bill’s life is, at its core, a love story:

At the Home, the patina of his memory covered life’s sorrows, and it was a blessing. Bill was happy there, living a life that was a strange mixture of hunting stories, pickup trucks and memories of some of his better times with women, friends and the outdoor life. Bill denied that anyone he loved had died; could not understand why anyone would fill with gas at four bucks a gallon when “Johnny’s Standard sells it for 27 cents;” and still “drove” his 1968 Dodge Charger. He was unfailingly courteous. His largest concerns were making his smoke breaks and finding his wallet (a search of 26 years).

In the past year, Bill’s shaky grip on physical health also slipped through his fingers. Yet, despite this, what we loved in him remained, if only sometimes as a shadow. Even after his serious decline, suffering fractures because of falls, Bill would tell the staff that he was “just fine” and not to worry about him. Thin, hunched over, propelling himself with one foot, he would wheel himself into the room of a bed-ridden veteran and sit there, next to the bed, unspeaking. The nursing staff was certain that Bill thought that the man in the bed was lonely and needed company.

Bill was always a proud man, remembering himself as he was in 1969, not as he became. Who are we to suggest differently? His was not a life that many would wish for, but in some ways, Bill was a lucky man. He was surrounded to the end by staff who enjoyed and respected him. He had a chance to be helpful to others who were doing less well than he. And the passing of the seasons never diminished his plans for another elk hunt or to “see that beautiful girl again this weekend.”

When a small slice of reality penetrated his pleasant confusion, Bill struggled to understand why he was where he was. Prematurely aged, his worldly goods in a small dresser, not knowing who the President might be or remembering why he should care, Bill’s losses were greater than most of us could endure. Yet, to those who love him, his brother and his brother’s wife, and their sons, he will always be a brave, accomplished man, more generous than was wise, more trusting than was safe.

It is not possible to wrap your arms around a loved one who leaves. But it is possible to wrap your heart around a memory. Bill’s will be well taken care of.

I read every word of Bill’s obituary no fewer than five times. I read it aloud to my husband. I texted it to my mom and dad; shared it with my friends.

And it didn’t take me long to send a message to the email listed at the conclusion of the obit, in search of the author whose words had so moved me.

When I heard back from Paul Ebeltoft, for the second time his words stole my breath: “Bill was a very great and very talented guy who failed to receive the good luck with which I have been blessed. As I was writing his obituary, I found I was writing to tell of Bill but also to remind myself anew of the unearned happiness I enjoy and to thank him for his part in securing it for me.”

Bill may have lost his life all those years ago in Vietnam, but his life never lost its value.

And in the final analysis here below, that may just be the only thing that really matters.

P.S. Hey Bill, I hope you found your wallet.

Remembrances can be shared directly with the family by email to [email protected]. Anyone who is so inclined is encouraged to donate to Stark County Veterans Memorial Association at P.O. Box 929, Dickinson, North Dakota 58602. A private service, through Stevenson Funeral Home and Crematory, Dickinson, will be held in the spring.

RELATED: She Lived To Be 105 and This Mantra Got Her Through

If you liked this, you'll love our book, SO GOD MADE A MOTHER available now!

Order NowCheck out our new Keepsake Companion Journal that pairs with our So God Made a Mother book!

Order Now